Indoctrinated by plants: Uncut

EGA’s Dr Liam Engel takes Dr Prudence Gibson on a tour of the Australian psychedelic environment, exploring plant sentience, conservation and reform. A shorter version of this article has been published by Wonderground.

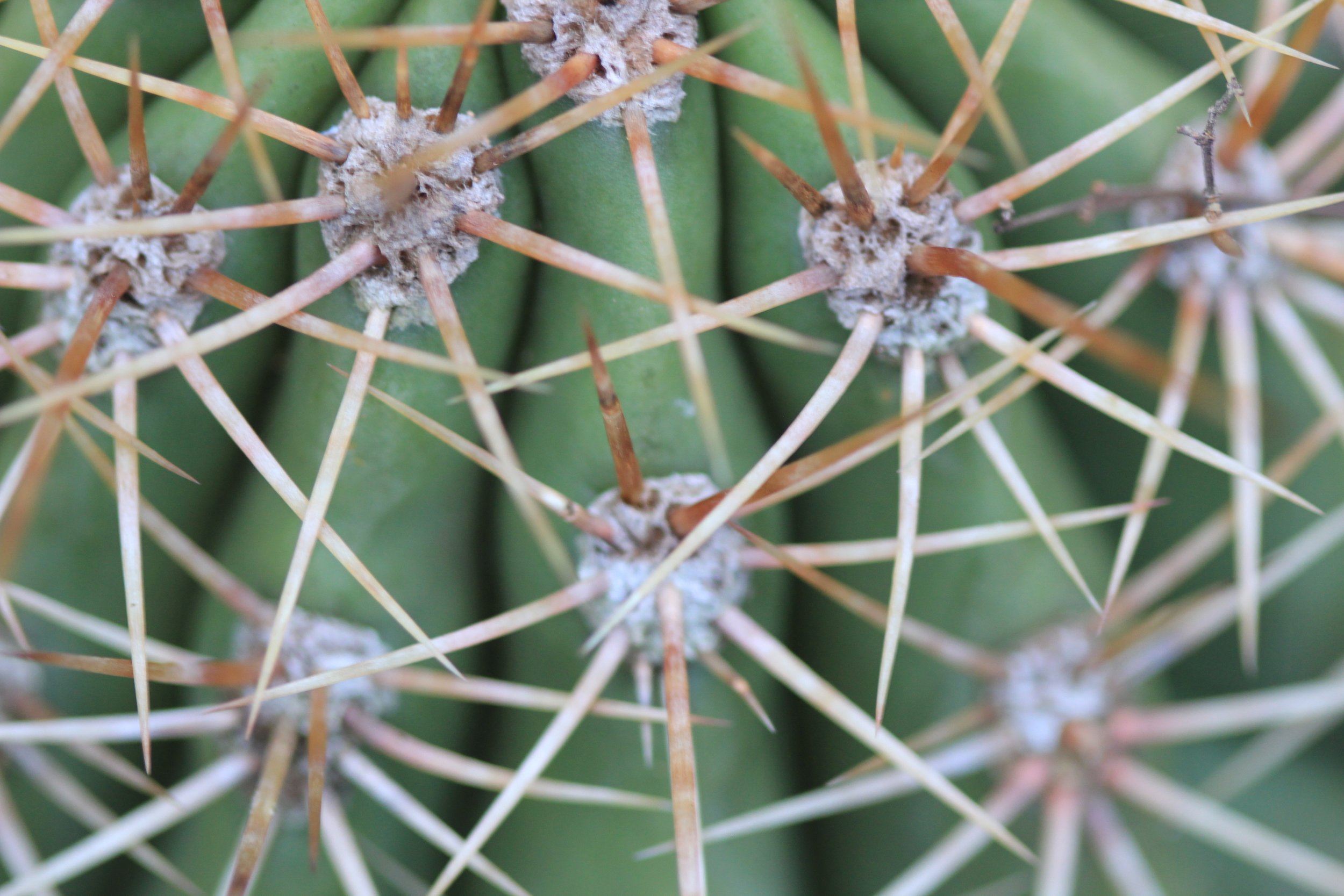

Trichocereus terescheckii. Photo by Liam Engel.

In recent years, there has been a boom of interest in psychoactive plants - plants that change consciousness when imbibed. We might call this a boom of entheobotany.

Ethnobotany refers to cultures of plant use, while entheogen refers to the experience of divinity. The term entheogen emerged due to criticisms of words like narcotic and psychomimetic, which carry negative connotations about drugs. Psychoactive drugs or entheogens, including psychoactive plants, offer both opportunities and threats, but these threats are greatly exaggerated by drug negativity and stigma.

Interestingly, entheobotany is viewed with less stigma and more positivity than other drug cultures. This may be due to curiosity around psychedelics, altered states, alternative medicine, First Nations traditions, plant-based preferences and/or the idea of “growing your own.” Entheobotany also recognises the positive contribution of drugs to broader issues of environmental and social justice, including grassroots conservation and propagation initiatives, as well as peer-led harm reduction efforts.

“Would we, for instance, even be able to hear their message, if the plants were trying to tell us that environmental equilibrium required human extinction or population controls?”

Entheobotany tells us that some of our human stories and relationships with plants need to change. The story of Adam and Eve’s eviction from the Garden of Eden highlights an age-old obsession with discovering a divine state of environmental and social innocence. Edenic narratives refer to stories or experiences that have a sense of nostalgia for a lost paradise.

These kinds of stories, with an aesthetic and ethical tone of loss, suffering, betrayal and human domination over nature, contribute to a 21st century longing to return to a time of plenty and order. Of course, this kind of thinking slips into an unnatural fable, a morality tale that forgets the damage wrought by humans (particularly extraction industries) upon the natural world.

Edenic narratives have been co-opted by those who want to promote sustainability or biodiversity in an effort to re-value human-nature relationships. Within the context of entheobotany, the Edenic narrative implies that the development of human/plant relations via experiences of altered consciousness may save humanity from extinction.

The danger for entheobotany is that Edenic stories trip humans up, as these stories promote unhealthy, masterful and non-Indigenous relationships with the land, viewing the environment from a human-centric perspective. Would we, for instance, even be able to hear their message, if the plants were trying to tell us that environmental equilibrium required human extinction or population controls?

Lophophora williamsii, AKA ‘Peyote.’ Photo by Liam Engel.

We can’t know what plants think or say, and there are other complicated human-plant themes of dispossession and resource extraction that permeate the history of entheobotany. The classic example is U.S. ethnomycologist Wasson’s 1958 publication of Life magazine, which publicised previously secret Mazatec traditions involving psilocybin mushrooms. This resulted in tourists flocking to Oaxaca, damaging the local environment, creating tensions within the local Mazatec community and between this community and the broader public.

While people have since realised how widespread psilocybin mushrooms are, meaning they are less likely to travel internationally to find these mushrooms, these types of damages and tensions remain prolific in the entheobotanical tourism industry, quite clearly in the present case of ayahuasca. As Edenic narratives place nature under human dominion, entheobotanical tourism also subordinates entheobotanical cultures. Seeking a ‘genuine’ or ‘traditional’ ayahuasca experience can be a particularly colonial act, creating external pressures on local culture, as well as the local environment, as they become market commodities.

But there is good news. There is a growing body of research evidence that suggests psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy could be useful not only for the treatment of a variety of mental health conditions, but even for the improvement of wellbeing in healthy people. This research has generated economic interest in psychedelic medicine, including pharmaceutical companies and training providers, which has in turn influenced media and brought public attention to the topic.

“Seeking a ‘genuine’ or ‘traditional’ ayahuasca experience can be a particularly colonial act, creating external pressures on local culture, as well as the local environment, as they become market commodities.”

However, the minimum standard of evidence for bringing a new medicine to market is a phase three clinical trial, which assesses efficacy, effectiveness and safety of a drug. At the time of writing there is only one such psychedelic trial that has been completed with promising results, a study of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While there are an increasing number of psychedelic clinical trials, research for psychedelic medicine is in the early days.

At present there is insufficient evidence for the use of psychedelics other than MDMA as medicines for the treatment of conditions other than PTSD, as well as for the use of psychedelic medicines without the accompaniment of psychotherapy. It seems likely that this evidence will grow, and such evidence would surely be followed by further entrepreneurial investment and development in the psychedelic space, but the evidence isn’t quite there yet…

The medicalisation of psychedelics is a divisive topic. Many argue that legalising psychedelic medicine provides no real benefit to people who use psychedelics due to prohibitive costs and bureaucracy. Some appear hopeful that psychedelic medicine provides a legal pathway for these drugs that could in turn encourage change to harmful, prohibitive drug policies. Others feel medicalisation will create an additional barrier to decriminalisation and/or other alternative drug policy models such as legal recreational markets.

The drug reform movement is underpinned by broader discourse around identity politics. Improved literacy concerning race, sexuality and gender has equipped many people with the ability to critique unequal power relations, to speak out against oppressive politics and to speak up about their stigmatised personal choices. The majority of harms pertaining to all illicit drugs, plant-based or not, stem from the interwoven forces of stigma and prohibitive drug policy, and through the increased ability of people to recognise and identify with this power struggle, drug policy liberalisation and critiques of prohibition are gaining momentum.

“The majority of harms pertaining to all illicit drugs, plant-based or not, stem from the interwoven forces of stigma and prohibitive drug policy”

Entheobotany features heavily in this reform movement, most obviously via the influence of cannabis, which is increasingly accessible for medical and recreational reasons throughout the world. In the U.S., the ‘Decriminalise Nature’ campaign has been followed by a number of jurisdictions reducing restrictions around psychoactive plants, in particular psilocybin mushrooms and other natural sources of psychedelics. In Australia, there has recently been attempts to have the Therapeutic Goods Administration reclassify MDMA and psilocybin as medicines.

As a plant-studies researcher and a drug communications scientist, we explored Australian entheobotany both conceptually and literally, in-situ and ex-situ, amongst the plants and fungi of western Sydney. We present our exploration in three vignettes, each focused on a different natural source of psychedelics; psilocybin mushrooms, mescaline cacti and DMT Acacia. We emphasise the effect the renewed passion for psychoactive plants is having on native habitats and conservation efforts. The communicative capacity of plants, considering research that suggests plants can learn and remember, provokes consideration of how plants might transform environmental relations. Perhaps it is optimistic, but we hope that psychoactive plants influence human consciousness in a way that improves how humans treat both the environment and one another.

Panaeolus cyanescens, a less common Australian magic mushroom. Photo by Liam Engel.

Psilocybin mushrooms.

Psilocybin mushrooms are likely the most well-known natural source of psychedelics. ‘Like mozzies, psilocybin mushrooms have been called ‘anthropophilic’ meaning they have a preference for human habitats. Where people go the mushrooms follow, or maybe it’s the other way around…’ Liam tells me this piece of trivia as we walk along a fire trail that runs between a pine forest and a national park, pointing to the edge of the track. ‘I see more of them where there have been people – like beside the path we’re walking on, rather than deep in the bush, and I’ve seen much bigger patches in commercial forests and woodchip garden beds than in the bush.’

Liam is taking me to see native, wild psilocybin mushrooms, specifically Psilocybe subaeruginosa, which Liam refers to as ‘subs’. The most internationally famous psilocybin mushroom, Psilocybe cubensis (‘cubes’), aren’t quite as well known in Australia as subs, likely because wild subs are more common than wild cubes around most of Australia’s largest cities. Most wild Australian cubes grow in Queensland and Northern NSW.

“In one way it is great that more people are interested in these species, but in another way this psilocybin mushroom demand creates new environmental pressures.”

White, cobweb-like fibres can be seen on decaying wooden debris. This is mycelium, the fibrous network giving fungi the capacity to grow in enormously distributed ways underneath our feet. Mycelium is connective tissue that winds between the roots of multiple trees, sharing nutrients and information across the entire forest floor – the mushrooms themselves are the fruits of the mycelial tree, and their spores are the seeds.

I spot a large, iconic red and white mushroom. I’m told it is magic, but not psychedelic, containing muscimol and ibotenic acid, rather than psilocybin. ‘Those mushrooms have to be prepared properly and they work on your GABA receptors, like alcohol or valium, rather than on your serotonin receptors, like psychedelics.’

It is unlikely medicinal psilocybin would be derived from natural sources, but media around this issue has renewed public interest in psilocybin mushrooms. ‘In one way it is great that more people are interested in these species, but in another way this psilocybin mushroom demand creates new environmental pressures. At the same time these mushrooms are illegal, which makes it hard to organise the Australian community around psilocybin mushroom conservation.’

Psilocybe subaeruginosa, Australia’s cold weather magic mushroom. Photo by Liam Engel.

Mescaline cacti.

Some cacti enthusiasts might not know it and others may not admit to it, but most of them have at least a little bit of mescaline somewhere in their gardens. The two most common mescaline cacti are San Pedro and Peyote. San Pedro grows quickly and is prolific in the wild, whereas Peyote grows very slowly and is dwindling in numbers. Encouraging recreational consumers to choose San Pedro over Peyote can help conserve these plants.

As Liam takes me to visit cacti gardens throughout the western suburbs of Sydney, Liam explains which cacti people prefer to consume. They point out a short form TBM (Trichocereus bridgesii monstrosa), otherwise called the ‘penis plant’ (no offence intended – this is a common name – ‘Frauenglück’ in German). This plant can be found throughout the world and am told by the owner that it is ‘good food’, that is, it has a potent mescaline content. Cacti with ‘monstrosa’ forms are also seen as highly valuable by collectors. It feels as if there is more room to celebrate physical difference in cacti culture than human culture.

“It feels as if there is more room to celebrate physical difference in cacti culture than human culture.”

We ask the owner of one garden why he started it. We won’t mention the gardeners’ names. His answer: ‘to eat it all.’ He tells us he first ate a cactus back in 2014. After a few dud experiences he learned to choose the right plants, refined his brew technique and has grown his own ever since. His garden has hundreds and hundreds of plants. All in neat rows, some up in garden beds. We see innumerable bright yellow, variegated pups, fresh cuttings callousing on drying racks and grafts healing, rubber bands firmly holding scions in place. The collection is almost entirely different species of San Pedro and Peyote. Some of these cacti came from mother plants over 100 years old, perhaps much older. Many of these plants have been used psychedelic traditions for generations.

Liam jokes that the cacti gardener is known for being the ‘tersch connoisseur.’ Trichocereus terescheckii (‘tersch’) are very thick, and by weight they contain less mescaline than typical San Pedro. ‘Only the connoisseur and Andean indigenous people can be bothered to eat that one.’ The tersch connoisseur describes a process whereby he removes the dark layer of green cacti flesh under the skin, avoiding spikes, and makes a cacti soup.

The second garden we visit features a massive ayahuasca vine out the back, which has strangled one tree to death and climbed five meters or so up another. We learn that this is the oldest ayahuasca vine in Australia. The owner of this garden tells us he spent some time with a shaman in Peru in the early 90’s, and that the shaman gifted him a cutting of the vine, as well as cuttings from three San Pedros and two San Pedro seed pods. ‘These were the shaman’s favourite plants. People say bridgesii are the strongest San Pedro, but the peruvianus the shaman gave me is the strongest I’ve ever had.’ Trichocereus bridgesii, Trichocereus pachanoi and Trichocereus peruvianus are the three species most commonly identified as San Pedro.

“People say bridgesii are the strongest San Pedro, but the peruvianus the shaman gave me is the strongest I’ve ever had.”

The result, 20 years since he started his collecting, is an acre of garden crammed full of succulent mescaline. We start to wander amongst all of his old and thick cactus. Huge old blue columns. He tells us that the v-marks on the cactus shows their age. One ‘v’ is one season of growth. Like rings of a tree trunk. We move to the other part of the large garden, to see inside some large greenhouses and stop to talk to the second gardener’s mother. She is seated in front of a spikey large ball called a Ferocactus latinspinus. The ball of cactus is three times the size of the spikey ball I have at home and, with gloves on, the woman whistles to a crowd of magpies while using huge tweezers to pull out weeds. She’s almost 90 years old but continues to spend most of her time caring for their giant family of cacti. I wonder if she knows she is carrying on a mescaline tradition that may have been passed down for thousands of years…

Trichocereus pachanoi, AKA ‘San Pedro.’ Photo by Liam Engel.

DMT Acacia.

DMT is so prolific in the Australian native landscape that it makes an appearance on the national emblem, in the shape of a wattle tree. There are many, many different types of wattle, taxonomically referred to as Acacia species. Each species contains a different amount of DMT, and this potency can vary depending on the environment the tree is grown in, the time plant material is harvested as well as other factors.

Within the entheobotanical community it is understood that selecting a wattle for psychedelic purposes requires some specialist knowledge. While choosing DMT wattle has become a lot easier than it was in the 90s, knowledge of the psychoactive properties of these trees has placed pressure on vulnerable species of Acacia.

“...there are two common Acacia species that people can preference to protect other, rarer and more vulnerable Acacia”

Liam explains to me that, like encouraging people to choose San Pedro over Peyote, there are two common Acacia species that people can preference to protect other, rarer and more vulnerable Acacia, such as Acacia phlebophylla, or phleb. ‘If they insist on wild harvesting then its Acacia acuminata on the west coast, Acacia obtusifolia on the east, that’s what people should be choosing.’ While wasps, rot and fire that have been impinging on phleb populations for some time, it was not until the 1990s that the public realized DMT could be extracted from these trees, adding additional pressure on the small, endemic population of phlebs.

These days phlebs are growing in Entheobotanists’ gardens all over the country. Ronny and Caine, active members of Entheogenesis Australis, both have healthy phleb trees growing in their backyards. Wild harvesting of phlebs has slowed down now people are aware of other, more common Acacia species that also contain DMT. Yet there is a more recently popular endemic Acacia that has become threatened by DMT harvesting. Liam won’t tell me the species name, for fear it will encourage further wild harvest. ‘We started the Conseracacian project to protect these vulnerable trees with a simple message – preference DMT made from cultivated rather than wild Acacia. Sure, if you must wild harvest, only collect fallen material and choose acuminata or obtusifolia, but we prefer to promote consumption practices that have minimal impact on native environments.’

Acacia phlebophylla. Photo by Jonathan Carmichael.

This is the state of entheobotany. The line between people and their environments is imagined. We are certainly animals, and perhaps we are also plants. Indeed, this is what psychedelics so often show their consumers. A monotheistic psychedelic message often leads people to conclude that we are all one. Liam and I hope the entheobotanical boom will lead to greater care, strategic conservation and increased respect for different approaches to plant-human relationships. We dream of providing plants with the same level of care we provide ourselves.

“The basic problem is to understand that there are no such things as things; that is to say separate things, separate events. That is only a way of talking. What do you mean by a thing? A thing is a noun. A noun isn’t a part of nature, it’s a part of speech. There are no nouns in the physical world. There are no separate things in the physical world either.”

Dr Prudence Gibson is an author and academic at the School of Art and Design, University of NSW, Sydney. She is Lead Investigator of an Australian Research Council grant in partnership with Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens Herbarium. Her recent books are Janet Laurence: The Pharmacy of Plants (NewSouth Publishing 2015), The Plant Contract (Brill Rodopi 2018), and her forthcoming book with NewSouth Publishing, The Plant Thieves, will be published in February 2023.

Dr Liam Engel is a drug communications scientist, harm reduction advocate and entheobotanist. Liam is a core Entheogenesis Australis contributor, Associate Editor of AOD Media Watch and adjunct research fellow at Edith Cowan University’s School of Medical and Health Sciences. Their recent publications include Presence, trust, empathy: Preferred characteristics of psychedelic carers (Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2022), Reference Guide for Lophophora Conservation (Entheogenesis Australis 2021) and Positive drug stories: Possibilities for agency and positive subjectivity for harm reduction (Addiction Research and Theory 2020).