Melbourne's Forgotten Psychedelic Era - Part One -

The Dawn of Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy, Research and Hallucinogenic Experimentation

Introduction

The Good, the Bad and the Forgotten

The early history of Australian clinical research into psychedelic-assisted therapy using psilocybin and LSD has largely faded from memory. With the current resurgence of interest in the therapeutic potential of these substances, it’s surprising that such a pivotal chapter remains obscured in historical accounts and collective memory. This oversight might be due to the passage of time, the radically different societal context of those earlier decades when experimental medical practices were more common and documentation less rigorous, or the complexity of the stories themselves.

This article explores the pioneering work during the late 1950s to 1975, detailed in Part One, when Melbourne's Newhaven Private Hospital became a hub for early psychiatric experimentation. Psychiatrists like Dr Lance Howard Whitaker explored the potential of psychedelics to revolutionise mental health treatment. However, these efforts became entangled with the infamous cult, “The Family”, illustrating the ethical challenges and societal backlash of the era.

Within this turbulent landscape, there were narratives of profound personal growth and self-realisation, such as that of Evelyn Harrison, whose story is covered in Part Two. Harrison, a resilient and courageous young mother, underwent psilocybin-assisted therapy in Melbourne, Australia, during the 1960s. Her journey, set against the sociocultural, medical, and legal contexts of the time, highlights the dual nature of psychedelic use: its transformative potential alongside the tragic consequences of its misuse.

Part Three delves into the darker side of this history, examining how the misuse of LSD by The Family and its leader, Anne Hamilton-Byrne, exploited the vulnerabilities of psychedelic research. This part of the article seeks to uncover these complex stories, highlighting both the beneficial effects of these potent substances and the darker chapters of their history.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration's 2023 decision to allow limited access to psilocybin in Australia for treatment-resistant depression underscores the persistent demand for innovative treatment options, bolstered by contemporary research in the field. While only time will reveal whether the benefits outweigh the risks, the reintroduction of psychedelics into the clinical setting offers new hope for patients in need. However, accessibility remains a significant issue that must be addressed to ensure that these treatments are available to all who could benefit from them.

As interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics resurges, this story delves into the broader context of Australia's early psychedelic history, examining the roles of psilocybin and LSD not only as agents of transformation but also as forces of disruption and, in some cases, harm. The lessons that can be drawn from this history, whether positive or negative, are as pertinent today as they were in the past, offering valuable insights as we navigate the complex landscape of psychedelic therapies in the 21st century.

Part One

Opening Doors: Tools of the Mind

Albert Hofmann

Albert Hofmann, a Sandoz chemist, synthesised LSD-25 (lysergic acid diethylamide) in the course of his work with ergot fungi in 1938. It was another five years, in what is now a famous accidental self-dosing, before he discovered the uniqueness and potential of his creation firsthand.

After self-experimentation, and as others tried LSD, Hofmann soon recognised that it could play a significant role as a psychiatric tool. He noted that, “LSD, a new active compound with such [profound] properties, would have to be of use in pharmacology, in neurology, and especially in psychiatry, and that it would attract the interest of concerned specialists.” (Hofmann, 1980, p. 14).

Undeterred by his accidental discovery of the potentials of LSD and motivated by his successful explorations with psychedelic plants and fungi, Albert Hofmann persisted in his research into psychedelic compounds. In 1958, following the receipt of a sample of the sacred mushroom Psilocybe mexicana from mycologist Roger Heim (whom had grown the sample after having received specimens of the mushrooms on an expedition with Gordon Wasson in Oaxaca Mexico), Hofmann successfully isolated two key psychedelic compounds that are central to our discussion: psilocybin and psilocin.

Albert Hofmann holds a model of an LSD molecule (Novartis Company Archives)

Experimentation

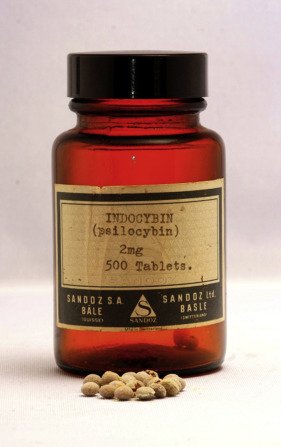

Following the Second World War, psychiatry was a rapidly evolving field. The introduction of new psychedelic drugs for experimentation is often credited with revolutionising the study of psychiatry and the human mind, parallel to the transformative impact of the atomic age on science and technology during the late 1940s and 1950s. Recognising the potential of these substances, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals made LSD available to the medical and research communities under the trade name Delysid, and psilocybin tablets under the trade name Indocybin, positioning these new tools as experimental drugs. This initiative aimed to gather more data to better understand their medical and therapeutic potential.

Sandoz manufactured 2 mg psilocybin tablets under the trade name Indocybin (Psychedelic Science Review)

Sandoz encouraged not only the clinical use of LSD and psilocybin but also endorsed self-experimentation among psychiatrists, believing it to be crucial for them to experience their effects firsthand to comprehend the mental states of their patients better, and gain a deeper understanding of altered states and the inner workings of the mind. The guidelines provided with Delysid emphasised this approach, stating, “By taking Delysid himself, the psychiatrist is able to gain an insight into the world of ideas and sensations of mental patients.” (Hofmann, 2009, p. 73). This policy underlined a pioneering phase in psychiatric research, where direct experience by clinicians was seen as a valuable asset in developing effective mental health treatments.

New Hopes

Thus, a new era in psychiatry was born, where the use of these new pharmacological tools in conjunction with psychotherapy was seen as having great promise for unlocking the secrets of the mind. It was proposed that LSD could offer a better understanding of mental illness and possibly identify the biological causes of conditions such as schizophrenia, with the hope that lasting treatment might be discovered. It was widely thought that new discoveries in this area could significantly reduce suffering and help people manage their lives better. Dr Stanislav Grof, a pioneer in LSD-assisted psychotherapy, reflected on this era: “Those of us privileged to have personal experiences with psychedelics and to use them in our work, saw the great promise that…they represented not only for psychiatry, psychology, and psychotherapy, but also for modern society in general” (Grof 2009, as quoted in Hofmann, 2009, p. 15).

One of the lasting contributions of LSD research to neuroscience was in deepening our understanding of serotonin, a crucial neurotransmitter. It wasn't until the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the identification of the 5-HT2A receptor, that scientists started to grasp how LSD influences brain function by interacting with this receptor. This insight built upon earlier observations from the 1950s, which suggested that LSD affected serotonin pathways, influencing mood and perception. The detailed understanding of LSD's interaction with the 5-HT2A receptor has since informed the development of targeted treatments for psychiatric conditions such as depression and schizophrenia, marking a significant milestone in psychopharmacology.

Sliding Doors: Backlash and Countercultures

Resistance

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, psychedelics began to be viewed by governments and institutions as tools of societal disruption and substances to fear. Despite this, and against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, the use of LSD and psilocybin became more widespread, moving beyond the lab and into underground markets. Richard Nixon’s "War on Drugs" came into full effect as governments attempted to criminalise people who used drugs recreationally and targeted certain demographics who partook in these substances (usually of lower socio-economic backgrounds, students and people of colour). This sentiment of the time was best exposed by John Ehrlichman, a top advisor to President Richard Nixon;

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and Black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalising both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.” (cited in Equal Justice Initiative). ”

Anti-War Moratorium, San Francisco, November 15, 1969 (Synergetic Press)

Subcultures that embraced these mind-expanding substances were seen as radical movements beyond the control of the powers that be, leading to international moral panic around LSD and—to a lesser degree—other psychedelics.

For the government, Timothy Leary, an academic who became a radical, epitomised this sociocultural shift. He was dubbed “the most dangerous man in America” by President Richard Nixon, due to his psychedelic-inspired spiritual and philosophical incitements. Leary and his followers departed their academic positions and research in favour of taking psychedelics to the masses. The genie was out of the vial, and the world would never be the same again. Just as the dropping of the atomic bomb marked a seismic shift in global politics and power structures, the introduction of LSD catalysed profound disruptions in cultural and scientific perspectives, leading to lasting and unanticipated effects.

Timothy Leary and his wife, Rosemary Woodruff, holding a news conference in Los Angeles (1969). Credit: John Malmin, Los Angeles Times

Tools or weapons

LSD use and the fear of it were on the rise during this period and the skirmishes to determine its application went well beyond the lab and the underground. The public's understanding of psychedelics would come to be complicated further by the military-industrial complex’s experimentation with psychedelics as mind-control agents. For over two decades as psychedelic-assisted therapy was still formative years, the military in the UK and the USA conducted LSD tests on soldiers, many of whom were unaware participants and never gave their consent.

Perhaps the most notorious misuse of psychedelics was the CIA’s “Project MKUltra”, which aimed to determine if LSD could be used for intelligence extraction and later tested as a psychochemical aimed at incapacitating large groups of people. In a high-profile and controversial case, the White House formally apologised in 1975 for the events leading to the death of Frank R. Olson, who died in 1953 after the CIA administered LSD to him without his consent as a training exercise. Initially, it was believed that Mr. Olson fell from a great height, but theories have since emerged suggesting he might have been pushed by CIA agents to protect state secrets.

This period highlights the dual nature of LSD. As one historian summarised, “[LSD] has been used both as a weapon and a sacrament, a mind control drug and a mind-expanding chemical. Each of these possibilities generated a unique history: a covert history, on the one hand, rooted in CIA and military experimentation with hallucinogens, and a grassroots history of the drug counterculture that exploded into prominence in the 1960s" (Lee & Shlain, 1985, p. XXV). At times, these two histories overlapped, revealing the tension between LSD's use for control and its promise as a tool of liberation.

Governments and international organisations, including the World Health Organization, advocated for the outright banning of LSD and a crackdown on its proponents, who were often perceived as anti-war and anti-capitalist. As the medical establishment distanced itself from psychedelics, public demand for these substances grew within the underground scene. Black market sources rapidly emerged to meet this demand but the lack of proper education and safeguards led to rare but real harm through misadventure.

In Melbourne, Australia, the cult known as "The Family" (or Great White Brotherhood) is a particularly devastating and well-documented example of how LSD was abused and misappropriated by its spiritual leader, Anne Hamilton-Byrne, at Newhaven Private Hospital and other cult-owned properties. It was sensational cases like this and consequent public fear about LSD that fuelled widespread controversy around the psychedelic movement and ultimately led to its rejection in the mainstream. The perceived threat psychedelics posed to the establishment during the 1960s and 1970s left a significant and enduring impact on politics, law, science, and culture to the present day.

Anne Hamilton-Byrne in the trees at Lake Eildon in late 1970s (smh.com.au)

Closing Doors: The Banning of the Medical Use of LSD and Psilocybin

Regulation inbound

In Australia, psychedelics were first regulated in Victoria under the Poisons Act of 1964 as Schedule 4 substances, permitting their prescription only by licensed psychiatrists. By 1966, amid the growing cultural backlash against LSD, Sandoz Australia withdrew LSD, psilocybin, and related substances from distribution. A letter from the Sandoz director at the time, Aurelio Cerletti, describes the situation:

“In spite of all precautions, cases of LSD abuse have occurred from time to time in varying circumstances completely beyond the control of SANDOZ. Very recently this danger has increased considerably and in some parts of the world has reached a serious threat to public health…Taking into consideration all the above-mentioned circumstances and the flood of requests for LSD which has now become uncontrollable, the pharmaceutical management of SANDOZ has decided to stop immediately all further production and distribution of LSD. The same policy will apply to all derivatives and analogues of LSD with hallucinogenic properties as well as to Psilocybin, Psilocin and their hallucinogenic congeners” (Cerletti, cited in Hofmann, 2009, p. 86).

Entry of L.S.D. Approved- Under Controls, October 20, 1966 (page 8 of 40). (1966, Oct 20). The Sydney Morning Herald (1842-2002)

However, after a short pause of supply, it was clarified that LSD would be available in countries that assumed full responsibility for its use and regulation with strict safeguards.

This development prompted Victorian researchers and clinicians to lobby the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) to adopt much stricter regulation protocols in order to maintain a limited pathway for the therapeutic use of these substances. One of the key individuals behind the amendments to the Poisons Act was Dr Lance Howard Whitaker, who consulted at Newhaven Private Hospital in Kew, Melbourne, and was regularly employing LSD and psilocybin in his therapeutic practice at the hospital.

Dr Whitaker was a pioneer in the field of LSD therapy and research in Australia, initiating his work with LSD as early as 1954 by conducting psychedelic-assisted therapy on war veterans returning from Korea. Over the next two decades, Dr Whitaker pursued his mission to explore LSD's therapeutic potential. In the mid-1960s, he even travelled to Sandoz in Basel to meet Albert Hofmann—the “father of LSD”—in person. While Dr Whitaker was convinced of LSD’s healing powers, his enthusiastic advocacy often bordered on the evangelical. With this same persistence, in 1967, in an effort to ensure medicine remained available to patients, LSD and psilocybin were reclassified to Schedule 7, a category designated for substances with a high potential for harm that require special handling. This successful lobbying extended access to LSD and psilocybin for 19 registered psychiatrists in Melbourne for use with patients only. The new regulation prohibited self-experimentation. Due to Dr Whitaker’s dedicated lobbying for psychedelic access and the resulting changes in law, Sandoz resumed sending psilocybin and LSD to Australia for use by qualified psychiatrists, with the endorsement of the Minister for Health.

In 1971, the ratification of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances led to the formation of an international treaty in which signatory countries, including Australia, were required to create more direct and effective policies to fight the “drug problem". Due to political pressure, LSD and psilocybin’s application as ‘medicines’ was drawing to a close. By 1975, regulations had tightened significantly again, effectively prohibiting the therapeutic use of LSD in Australia, which aligned with stricter international drug laws. LSD could only be sought for strict research purposes within controlled clinical trials which required direct approval from the Minister for Health. It was evident that public sentiment, political opinions, and medical establishment views had shifted, now regarding the study and use of psychedelic drugs as excessively risky and without medical application. This caused the scope of psychedelic access to be drastically reduced and this area of research to fall out of favour from the mid-1970s for at least four decades in Australia.

Regulation to prohibition

By 1975, LSD, psilocybin, and psilocin were reclassified as Schedule 9 substances under the Australian Government’s Poisons Standard, overseen by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). This effectively prohibited their use as prescription drugs, placing them in the same category as heroin due to safety concerns. Consequently, all clinical applications were cancelled immediately, with no exceptions, and for nearly five decades, psilocybin was deemed to have no medical value according to the TGA. The Poisons Standard is a national framework that sets a baseline for the classification of substances across Australia. The TGA's oversight ensures a consistent approach to drug scheduling and classification nationwide.

The regulatory framework evolved further in Victoria in 1981 with the introduction of the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act, which amalgamated all previous regulations relating to the Poisons Act into a single comprehensive legal structure. This framework continues to govern the control and use of these substances in Victoria, balancing safety concerns with emerging medical research and adjusting to regulations as necessary.

Note: For those interested in further research around regulations in Victoria, also see the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008.

Underground communities and DIY culture

As policing and regulation increased, restricting the availability of psychedelics, underground counterculture began to emerge in Australia. This largely grew out of movements against the Vietnam War and various other activist and subcultural groups that began to make their presence known. They included student politics, First Nations land rights movements, environmental activism, DIY culture, the rock music ethos, the wellness movement, citizen science, drug law reform advocates, queer culture, the cooperative movement, intentional communities, Eastern and New Age religious movements, zine culture, permaculture movements and various back-to-nature philosophies such as deep ecology. A particularly notable example is the township of Nimbin, in the Northern Rivers region of NSW, which became a focal point for these intersecting ideas. Nimbin is home to Tuntable Falls, one of the first and longest-running intentional communities in Australia, which was formed after the Aquarius Festival in 1973. The Nimbin community underwent a transformation as a result of the counterculture, becoming a hub for environmental activism, drug law reform and alternative thinking. The town is the home of the Nimbin Hemp Embassy and hosts an annual cannabis festival called “Nimbin MardiGrass”.

An example of ethnobotanical student activism, University of New South Wales student newspaper article, 1980, October 29, p. 12. (Tharunka student newspaper). Note: For guidance on Australian mushroom identification, a good starting point is the Ethnomycological reference list.

In the 1990s, as technology developed and the personal computer became more accessible, the advent of the internet played a critical role in shaping counterculture movements. The underground techno-cultural movement that emerged across the globe was influenced by a diverse array of psychedelic experiences and counterculture movements that preceded it. These were shared at informal gatherings, street parties and “bush doofs” (outdoor dance parties in nature featuring electronic music), and fueled by a DIY mindset and the psychedelic art movement. However, there was one significant change that everyone could feel—the traditional division between audience and performer had dissolved. Everyone was encouraged to be a "participant" and actively contribute to shaping the event or gathering, creating a sense of unity and shared purpose. As Mark Angelo Harrison succinctly put it: “No longer a place to gaze up adoringly at some contrived act strutting about on a pedestal. The dance floor had been reclaimed by the people as a free social space: a place where people felt centred, balanced - together” (Harrison, 2023, p. 26). Over several decades, the outdoor party scene evolved from backyard experiments into a full-scale festival culture.

An academic underground community also emerged in parallel to the party scene, embracing DIY and citizen science philosophies to develop and hone skills related to the cultivation, culture, use and conservation of ethnobotanical plants and fungi. This community has sought a deeper understanding of altered states of mind, and the role of entheogens in culture, both ancient and contemporary, with a “grow your own and share your seed” mindset. Focusing on harm reduction practices, the community has worked to create a safe space for those advocating for drug law reform. It serves as a testing ground for topics not permitted in traditional academia, or beyond the scope of legal practice, and has supported the formation of a network of activists and underground researchers dedicated to reigniting psychedelic research in Australia. Also notable are online communities including Shaman-Australis and Bluelight as well as educational charities such as Entheogenesis Australis (EGA). Following an EGA psychedelic symposium in Melbourne, it was at an EGA workshop in 2010 with Rick Doblin (MAPS) that the organisation Psychedelic Research in Science & Medicine (PRISM) was conceived, which became pivotal in advancing the next chapters of the psychedelic research narrative in Australia.

Counterculture movements like the outdoor party scene, the ethnobotanical education community and internet forums have become significant elements of alternative subculture in Australia. These movements have fostered a community of like-minded individuals who value both the psycho-spiritual and recreational use of psychedelics. The collective interest and support of grassroots movements and community activism has been crucial in pushing for drug law reform, ethnobotanical conservation and increasing awareness of the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

Note: For those interested in a more indepth and current overview of the Australian psychedelic community we recommend you read “The Ultimate Guide to Psychedelics in Australia” and also ““The Hidden Roots of Australia’s Psychedelic Underground”

The Australian psychedelic renaissance

Despite a tumultuous history and false start, the recent re-emergence of research and clinical applications of psychedelic medicines, often referred to as the “psychedelic renaissance”, has taken a turn for the better. In Australia, this is exemplified by a 2020 study led by Dr Margaret Ross (St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne) and Dr Martin Williams (Psychedelic Research in Science & Medicine), who conducted a landmark trial of psilocybin-assisted therapy for anxiety and depression associated with terminal illness. This study has paved the way for a number of new psychedelic clinical trials in Australia.

Dr Margaret Ross and Dr Martin Williams on stage at Entheogenesis Australis Garden States Conference in 2022

The shift in the way psychedelics have been viewed by the public, along with growing research supporting their application in medicine over the last 5-10 years, led to a significant change on, July 1, 2023, the Therapeutic Goods Administration officially recognised the therapeutic use of psilocybin and MDMA by adding them to Schedule 8 (Controlled Drugs) of the Australian Government’s Poisons Standard. Although they remain in Schedule 9 (Prohibited Substances) in all other circumstances, this change allows authorised psychiatrists to prescribe MDMA for the treatment of PTSD and psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. This marks a cautious yet growing mainstream acknowledgement of the potential medical benefits of psychedelics, leading to increased interest and research in the field.

Author: Jonathan Carmichael

Jonathan Carmichael is the co-founder, conference director, and President of Entheogenesis Australis (EGA), a charity dedicated to critical thinking and knowledge sharing about ethnobotanical plants, fungi, nature, and sustainability. He has been the driving force behind EGA for over two decades and is also a founding member of the charity Psychedelic Research in Science & Medicine (PRISM). Additionally, Jonathan is a freelance photographer whose work has been featured in various exhibitions and publications. He is passionate about history and ethnobotanical activism, with a strong focus on social justice and environmental issues.